As a parent, it’s difficult to try to instill in one’s children a real love and respect for God. For some children, it almost seems like second nature. For others, it’s a constant struggle. Faith isn’t a thing like reading, where once a person has learned how to do it, that stays with them for the rest of their lives.

Mind you, I was an adult convert to the Orthodox Church, but one thing that has always fascinated me is lives of the saints. As a kid, I really liked biographies of people and I found a couple of people with whom I was so impressed that I read multiple books about them. I would think that it follows, then, that it would be a valuable endeavor to have high-quality books about saints geared toward kids at least at the 8-12 year old range.

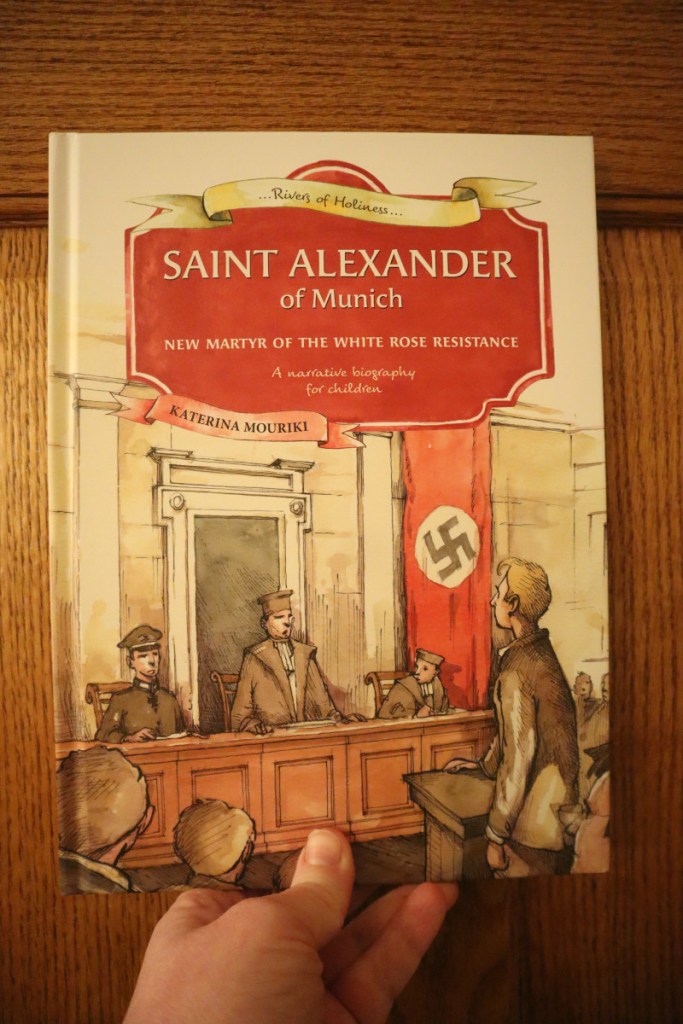

The book “Saint Alexander of Munich – New Martyr of the White Rose Resistance” by Katerina Mouriki is a book that tries to fill that gap. It’s part of a series of picture books geared toward older children called “Rivers of Holiness” and sold through Newrome Press. These books were originally published in Greek and then translated into English for these editions.

I’ve known this particular book has existed for quite some time, but I held off on purchasing it because it’s fairly expensive ($22, plus shipping) and knowing as much as I do about St. Alexander, I was afraid that I would hate it.

Well, I don’t hate it. However, I do think that there are real issues with this book, some of which are narrative, some factual, and some of which may come down to translation issues.

First off, I understand that with writing for children, having stories about a person’s childhood is extremely helpful. Unfortunately, in the case of Alexander Schmorell, there isn’t a lot that is out there about his very early life. His mother died before he was two, and Russia was in incredible turmoil during these years. In 1917 alone – the year in which Alexander was born – the tsar abdicated, there were two revolutions, and civil war broke out in Russia. In the next couple of years, add to this the murder of the royal family, widespread illness, such as typhoid, and chaos in the world. World War I was still raging (though Russia had pulled out in December of 1917) and 1918 brought about a worldwide pandemic of flu.

In the book, Mouriki introduces us to the Schmorell family – Hugo, Natalia, and baby Alexander. At first, I thought that maybe she was basing these scenes on research, but as far as I can tell, these early scenes are completely made up, much like the imaginary friends in the “ValueTales” books. I can overlook this to a large degree if it doesn’t conflict with actual facts because its a literary device, a way for characters to “come alive” even for little children.

However, there’s a scene in the book where Hugo and Elisabeth Schmorell (Elisabeth Schmorell being Hugo’s second wife, whose family, the Hoffmanns, were also well-off Germans in Russia) are supposedly discussing moving away from Russia “for the sake of little Alexander”. The reality of the situation was that the entire Hoffmann family – if I remember correctly, all eleven Hoffmann siblings, of which Elisabeth was one, plus all their spouses, children, etc – decided to leave Russia together in 1921. Most of Hugo’s family (he also had something like 10 siblings) were left behind in Russia. The move to Germany certainly wasn’t something that Hugo and Elisabeth decided alone.

Now, this may be nit-picking, but she also states that Hugo lied to “authorities at the border” to get Feodosia Lapschina to be able to accompany them. It sets up a scene where there’s high tension, like, “Will the lie be believed?” This never happened. The truth is much more complicated, and in twenty years, I’m not sure I know exactly what happened, but it’s more than likely that she was actually married to Hugo’s dying older brother in order to make her legally part of the family.

As we start getting into the Germany side of things, she makes a fairly big deal about how it was Alexander’s dream to study medicine like his father. I don’t think he hated medicine, and I think he absolutely had the intelligence and aptitude for it, but claiming that his dream was to study medicine is more than a little bit of a stretch. As somebody who is quite familiar with Alexander Schmorell’s life this is not a statement I would make. I don’t think that he hated medicine, but by and large, it seems that he saw it as a way to stay off the front lines more than anything else.

Mouriki claims that Alex proposed the name “White Rose” for the group as a reference to a scene in Dostoyevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov. Again, what? There is no definitive answer for us today as to why the group used the name “The White Rose”. I know of probably at least five suggestions that are more convincing than this one, but for whatever reason, this is the reason she chose, so she wrote the book this way.

In the section introducing the Scholl family, she introduces them with, “The Scholl family were Protestant Christians who were known for their faith and deeply held democratic ideals.” (p 24) Mind you, Magdelena Scholl had been a former Lutheran deaconness and was quite devout, but Robert Scholl, her husband, seems to have had no real use for religion, and was probably agnostic at best. The Scholl children were generally not interested in religion or faith until their older teen years, and a fair amount of that was due to the influence of a Catholic friend.

There is a kind of bizarre section called “The ‘White Rose’ Blossoms” (p 27-31) where Mouriki claims that Alex visits the Scholl siblings in their apartment on May 21, 1942. She makes sure to denote that it’s a Thursday as well, and claims that Alexander has been pondering the feast day of Ss. Constantine and Helen. This story is not only completely fabricated, but isn’t even correct. Alex’ church celebrated (and still celebrates) feast days according to the Julian Calendar! She also claims that it was at this visit that Alexander proposes that something must be done to counter what the Nazis are doing. THERE IS ABSOLUTELY NO EVIDENCE THAT ANY OF THIS HAPPENED! This section is almost 5 pages of the book! If you want to be *very* technical about this, on May 22, 1942, Alexander Schmorell wrote Angelika Probst to tell her that the day before (the 21st), he had gone to a concert and had met up with a friend and had some wine. He also wrote that on the 20th, he’d met up with Hans Scholl in Munich’s English Garden. It makes me wonder if the whole point of this was to give the book a Greek connection by randomly inserting a couple of Greek saints into the narrative!

In a statement on pages 33-34, Mouriki writes, “For Alexander and his friends, no guns or bombs were needed in the fight for truth. The Word of Truth Himself would be their weapon… ” Where in the world did this come from? In their own leaflets, they encouraged sabotage, but more than that, the men of the White Rose were known to have gone around armed, particularly when doing things at night. This is well known, and the statement just seems like wishcasting!

About halfway through the book, the word “justice” starts getting thrown around. On the last page of the story, for example, “A few hours later, Alexander Schmorell, a champion of the love and justice of Christ against Nazi atrocity, was killed by beheading.” Nothing against justice or God’s Justice or anything like that, but it seems like it’s a modern concept here inserted in. The members of the White Rose didn’t expect there to be any true “justice” under the Third Reich, but they did what they did because they knew it was the right thing to do.

Additional miscellaneous factual mistakes

- WWI was not already over in 1917, and the Russians hadn’t even pulled out until December of that year (p 7).

- Tsar Nicholas II was not murdered in 1917 (p 7).

- Hans, Alexander, and Willi were not sent to Stalingrad (p 38)

- Maybe a quibble, but the Soviets did not open up the churches with the Nazi German invasion, the Nazis allowed churches to open again under occupation.

- While an opinion, Mouriki claims that the Hans and Alex needed to write the leaflets in simple language so that people can understand them (p 36). This was not the case at all; the language used in the first four leaflets was so much at a high level that even Professor Huber, when he became involved, insisted that they tone it down.

- The dates for Alex’ arrest are wrong, as is the description of what he did to try to escape, and how and where it happened. IN A BOOK ABOUT THE MAN! (p 48)

Weird Details

- Mentioning Juergen Wittenstein early on, never to mention him again, but even when he had more of a role.

- Thilde Scholl was the seventh Scholl child and died before her first birthday. So yes, there were seven Scholl siblings, but writing about them like, “The seven siblings had a large group of friends…” is strange.

- She mentions the arrests of Hugo and Elisabeth Schmorell (they were actually arrested twice) but not the fact that his sister Natalia, only 16 was also arrested. All three of them became extremely, resulting in their release. However, Natalia, only 16, I believe, suffered a detached retina and went blind in one eye, but it’s just weird that she’d mention the parents but not the sister.

- In the timeline provided in the back of the book, the births of Alexander Schmorell, Christoph Probst, Hans Scholl, and Sophie Scholl are noted, but NOT Willi Graf.

Misspellings/mistranslations:

- MIsspelled names – Erich Schmorell, Feodosia Lapschina (while calling her “Theodosia” isn’t necessarily objectionable, the “th” sound doesn’t even exist in Russian), Elisabeth Schmorell, Angelika Probst, Elisabeth Scholl, at the very least

- Natalia Schmorell (Alex’ mother, not sister) died of typhoid fever, not typhus. (This gets very confusing since the German word for typhoid fever is Typhus.)

- “Hans and Sophie were captured and tied up.” (p 47) Arrested and detained, yes, but tied up?

- The translations of the snippets of letters and leaflets are not great. I suspect not only were they were translated from German to Greek, and then Greek to English, they were also “simplified” for suitability in a children’s book. One example, from Alexander’s last letter to his family – (German) – Nun hat es doch nicht anders sein sollen und nach dem Willen Gottes soll ich heute mein irdisches leben abschliessen…” (English, my translation) And now it has come to none other than this, that shall it be the Will of God my earthly life today will come to a close…” (Book translation) “Nothing more is going to happen now. By God’s will, my earthly life will come to a close today…”

I am really really thankful to have been given this book and take a look at it. The story of St. Alexander, in truth, is spellbinding. However, this book seems to fall into the category of dramatized histories of the White Rose like “Ceremony of Innocence” by James Forman and “Zu Blau der Himmel im Februar” by Jutta Schubert which take the real people and events of the White Rose and is not only false, but doesn’t do the original story or people justice. This is especially disappointing when the book is supposed to be telling the story of a saint; it’s like the author here understood the basic contours of the story of St. Alexander and was allowed to simply use her imagination to make up something that sounded good for the rest. It’s also disappointing that no one at Newrome Press caught the very basic factual errors that didn’t depend on someone knowing St. Alexander’s story, such as her assertion that Tsar Nicholas II was executed in 1917. (He was murdered in 1918.) I didn’t get into any of this here, but there are also assertions that are made in the book that may not be technically false, but they don’t represent the story as I know it (such as the story about the ROCOR Cathedral on page 53, which took an event that was actually miraculous and changed details to make it very mundane. Oh! And she didn’t take two minutes to research a date she mentions, because the date she has is wrong – 1990 vs 1992. *headdesk*)

We Orthodox desperately need stories for our kids, but seriously, we ought to be really careful that we’re creating quality materials. The book itself is quite nice, and I appreciate that there are a few real pictures included besides all the illustrations. However, when we tell the stories of our saints, it’s important to keep them “real”, warts and all, when that is the truth of the matter. I love St. Alexander dearly, but this book takes so many liberties and makes him so perfect that it’s hardly his story anymore. Not only is that sad, but I think that kids in the age group they’re aiming at eventually catch on to the inauthenticity as well.

If you enjoy my posts, please consider:

- Giving this post a “like”

- Sharing this post

- Subscribing to the blog

- Pledging monetary support

- Subscribing to my YouTube or Anchor.fm channels

- Patronizing the links that support this blog: Lilla Rose | Amazon

Thank you very much!

Thank you for taking the time to write such a thorough review. I’m certainly put off from buying any of this series from that publisher.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was considering contacting them just to let them know that there were issues with this particular book. As I was going through the website, I see that the publisher is a tiny house run by a priest in Missouri. Even more than that, his son who is also listed as working there at the publisher is someone I conversed with a little back in 2012 or 2013 (when he was a teenager) in conjunction with my work on Orthodox blogs and his work on another project. (Yes, the Orthodox world in the US is small!) I have nothing bad to say about them, and books like “O is for Orthodox” are gorgeous and well-done. I’d guess that part of the issue is that there probably isn’t nearly as much available on the life of St. Alexander in Greek as in English, German, or Russian, but he’s lived recently enough (and in Germany, no less, a country where everything is recorded – in triplicate) that there is a *lot* of information that is available simply because of that, making it much harder to just make up a nice story to “color” his life for kids. That being said, though, there were things that were just plain sloppy as well that somebody should have caught even in the Greek.

LikeLiked by 1 person